In Greek mythology life is represented by thread. There are three Fates. Clotho, the ‘spinner’, spins the thread of life from the spindle, this represents birth. Lachesis is the ‘alotter’ who measures how much thread is to be allotted to each person and Atropos the ‘inexplorable’ is the one who cuts the thread, death.

There are many depictions of the Fates throughout Art History. I’ve included this one, which lives at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, because it’s part of a larger tapestry that depicts a poem by the 14th century Italian poet Petrach called “The Triumphs” In the tapestry the Fates triumph death over a woman who represents chastity, this is the third part of Petrachs poem, ‘First, Love triumphs; then Love is overcome by Chastity, Chastity by Death, Death by Fame, Fame by Time and Time by Eternity.”

Athena, Goddess of reason, was believed by the Athenians to have invented weaving. Athena who was born of Metis, a quality most esteemed by the Ancient Greeks (metis is often described as cunning but it’s more than that, it’s being ‘born of wit.’) Weaving and wit therefore are undeniably linked. In Ovid’s version of “The Myth of Arachne”, Arachne is the daughter of a shepherd and a great weaver, who often boasts that her skill is greater even than Athena, refusing to admit or even acknowledge that some of her skill might have came from the goddess. This offends Athena who goes to Arachne, disguised as an old and decrepit woman and warns the young weaver not to compare herself to the gods. ‘Do not reject my advice: seek great fame amongst mortals for your skill in weaving, but give way to the goddess, and ask her forgiveness, rash girl, with a humble voice: she will forgive if you will ask.’ Arachne, however does not take the old woman’s advice and instead brazenly challenges Athena to what can only be described as a weave off, ‘I have wisdom enough of my own. You think your advice is never heeded: that is my feeling too. Why does she not come herself? Why does she shirk this contest?’ She practically calls Athena a chicken. The Goddess then reveals herself and accepts Arachne’s challenge.

In the English language there are lots of words and phrases that connect clothe making with storytelling. You can spin a tale, our thoughts and emotions can unravel, tangle or fray.

Athena’s tapestry glorifies all of the gods but herself in particular. Athena ‘weaves scenes of war, fate, the inexorable will of the God’s.’ Her tapestry serves as a warning to Arachne. Visually Athena’s tapestry is symmetrical with a clear centre and scenes in the four corners it also has a border. Athena ‘surrounded the outer edges with the olive wreaths of peace (this was the last part) and so ended her work with emblems of her own tree.’ This olive tree border is reflective of Athena’s ‘conviction that the universe is place of balance and order.’ Athena’s work shows the God’s of Olympia and their victories, how they conquer humans and turn them into animals. Arachne tapestry takes a very different stance to Athena’s, instead presenting the sins of the Gods, she depicts scenes of rape and deception. ‘In the twenty-four lines Ovid takes to describe her creation, twenty-one rapes occur. Jupiter is responsible for nine, Neptune for six, Apollo for four, Bacchus and Saturn for one each.’

Ovid does not present a clear winner. Both works are flawless but Athena angry at Arachne’s arrogance rips up her tapestry then beats her repeatedly. Arachne so ashamed hangs herself and Athena ‘in pity, lifted her, as she hung there, and said these words, ‘Live on then, and yet hang, condemned one, but, lest you are careless in future, this same condition is declared, in punishment, against your descendants, to the last generation!’ Departing after saying this, she sprinkled her with the juice of Hecate’s herb, and immediately at the touch of this dark poison, Arachne’s hair fell out. With it went her nose and ears, her head shrank to the smallest size, and her whole body became tiny. Her slender fingers stuck to her sides as legs, the rest is belly, from which she still spins a thread, and, as a spider, weaves her ancient web.’

The story of Arachne and Athena can serve as a warning to not challenge the system. However both women are able to present their personal worldview through their Art and although Arachne loses her freedom because of her “hubris” she is still able to share her Art for all eternity as a spider, this is both a blessing and a curse. Not to mention, Athena herself is also full of hubris, like Arachne couldn’t accept that some of her skill had come from goddess, Athena couldn’t accept the possibility that maybe Arachne was a more skilled weaver then herself. Yes, Ovid doesn’t present a clear a winner but that doesn’t mean there wasn’t one. Maybe Ovid censored his work too, the story makes a powerful point about censorship. Arachne’s work is destroyed and from a contemporary feminist perspective, it could be argued that she is ultimately punished for not staying in her lane as a mortal woman from a working class background. Arachne has the Artistic freedom to depict whatever she wants however her punishment for angering the Goddess is being trapped. Arachne is a feminist character, Her tapestry is full of images showing the gods deceiving or mistreating women, in this way she is speaking truth to power. However although she has Artistic freedom through her weaving she loses her actual freedom, condemned to live as a spider for all eternity. The link between weaving and storytelling can be further observed, the story of Arachne’s punishment mirrors Ovid’s own life. Ovid was banished by Augustus to the black sea where he stayed until his death. It’s one of the greatest mysteries of literary history as to why the poet was exiled but many historians believe it was because of the ‘objectionable ature’ of his poetry and he was being censored.

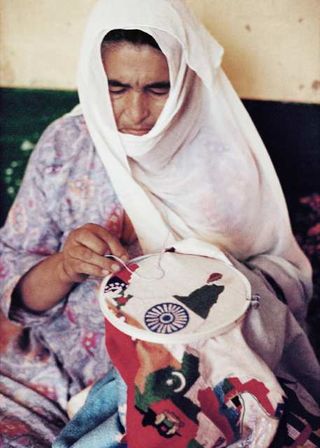

A contemporary example of weaving and artistic autonomy would be the Italian artist Alighiero e Boetti. In 1971, Boetti went to Afghanistan to collaborate with Afghani artisans, he began by asking a group of local craftswomen to create two embroideries, he wanted one to be embroidered with,“December 16, 2040” (the 100th anniversary of his birth) and the other with the text “July 11, 2023” (the date he predicted he would die.) The Afghan women surprised Boetti by straying from his design and adding flowers and other decorative flourishes. Boetti was intrigued by the idea of just letting the women be free and seeing what happened in regards to the finished product.

Boetti’s most famous work from the textile project is this embroidered flag, the piece started as a printed map of the world that he had bought from a shop and coloured in with crayons and inks. Boetti then commissioned a seamstress from Afghan to create an embroidery of the map. ‘Boetti’s maps unfold complex layers of social and cultural history, embodied in stitchery that ranges from highly refined and intricate to more haphazard and schematic. Vast oceans tend to be irregular, not to mention rarely blue, as spools of thread run out and dye lots change, creating unpredictable color blocks. Multiple hands did the stitching, often over months or even years.’ The border around Boetti’s map is reminiscent of the border around Athena’s tapestry and borders, ownership and sovereignty are major themes throughout his work.

Traditionally weaving and clothe making had been seen as a craft rather than an art form. This is potentially what lead to weaving being seen as a woman’s median. However it all really depends how you define ‘craft’, some people would argue that weaving is a craft because it creates a useable product, a tapestry lives many lives, it can be put up on a wall to admire, placed behind a king as a status symbol or laid on the floor as rug. I read on the Tate website a comment by user Tracy Fiegl that ‘comparing art to craft is like comparing philosophy to engineering’ because ‘they’re two separate ways of looking at the same thing.’ A tapestry can be viewed as an ornament but it can also have a function, it’s functionality does not negate its ability to translate an idea. ‘Functional objects can still communicate ideas, so art can be functional.’ My first time really seeing tapestry as an art form was when I was a little girl and my mum took me to the V & A to see the Raphael Cartoons. Not until years later when I saw the completed tapestries at the Vatican City, Rome would I truly appreciate the skill needed to complete them. These huge all-consuming works would be cut into strips and given to individual weavers to work on, ‘Because of the expensive materials and expert labour required for its production, tapestry was generally regarded as a more prestigious art form than painting during the Renaissance.’

Similarly to Arcachne and Athena the myth of Procne and Philomela as told by Ovid, presents women weaving. The monstrous Teureus is a tyrant from the land of Thrace. Teureus liberates Athens from the barbarians and then goes on to marry Procne, the daughter of their King. The marriage is doomed from the start because The Fates do not attend. One year into marriage Procne is unbearably lonely and pleads with her husband to return to Athens and fetch her dear sister, Philomela. However on the journey home the deplorable Teureus savagely rapes Philomela and holds her captive within an abandoned hut. Philomela threatens to tell everyone Teureus’s terrible crime so to prevent this he cuts her tongue out and upon his return tells Procne the heart breaking news that her sister had died on the voyage home. He silences her and and he believes he’s gotten away with it but Philomela desperately begins to weave a tapestry that helps her reclaim her voice by describing through Art what had happened to her and where she could be found. Procne saves her sister and together they plot revenge against Tereus.

1636 – 1638. Oil on canvas

This painting by Rubens shows the sisters revenge, after they murder Tereus’ son Itys and feed him to him for dinner. Philomelo then enters the room brandishing Itys’ severed head as proof of what they’ve done.

We can also look at weaving from from a social perspective, in Ancient times only women weaved so in many ways it became its own language, a language that was controlled by women. Women had their own chambers at the back of their houses built for weaving that men didn’t have access to called ‘gynaikonitudes.’ Penelope, sews by day and unpicks by night in her private chamber, a funeral shroud for her dying father in law. She tells her suitors that once she has finished she will choose one of then to marry, really she is biding time until her husband (presumed to be dead) returns. Penelope uses both metis and her Art to hold onto her freedom as long as possible. Men in Ancient times did not understand the intricacies of cloth making meaning Penelope was able to trick the suitors for nearly four years.

This ceramic dates back to 440 BC

This ceramic above shows Penelope sitting in front of her loom in anguish at the unknown fate of her most beloved husband Odysseus. ‘Her head is bowed and legs are crossed in a pose canonical for Penelope.’ Despite this Athenian red-figure cup which depicts Penelope as a victim, resigned to her fate, we know what she’s really up to.

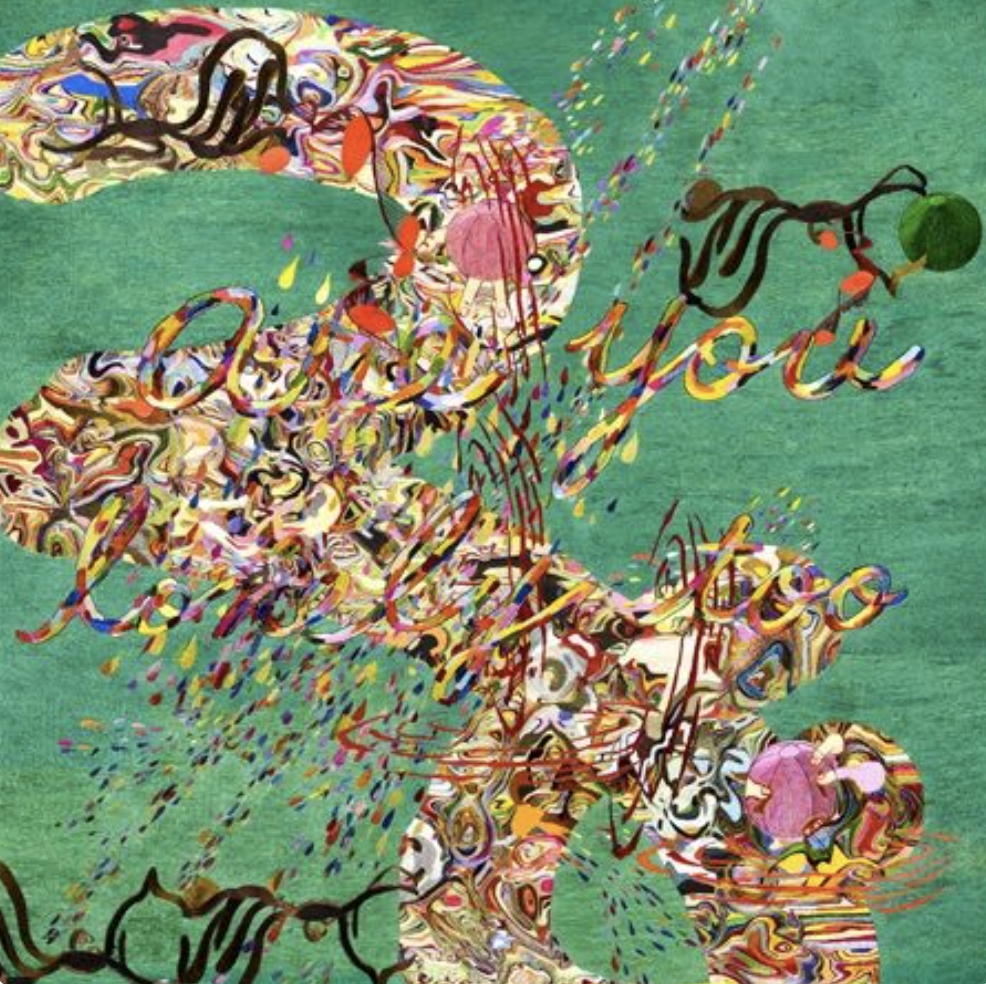

Many contemporary female artists continue to use weaving within their work as a form of resistance. The political diarist and contemporary artist Kyungah Ham’s work ‘Needling Whisper, Needle Country’ is an embroidery project where the artist who is from South Korea sends work to North Korea. The artist tries to communicate across the North Korean/South Korean border using ‘anti-propaganda.’ Kyungah Ham collects ‘international and domestic articles about war and terror and then revised their tone of voice into an antiquated North Korean style with Sung Ki-Wan, the poet.’ The artist sneaks the work through the border and then they are embroidered to reveal messages from the outside world. Unfortunately most of the finished pieces were confiscated by the North Korean government. The artist was fascinated with this long process to receive when in the ‘highly digitised world’ we can usually access this news in the click of a button.

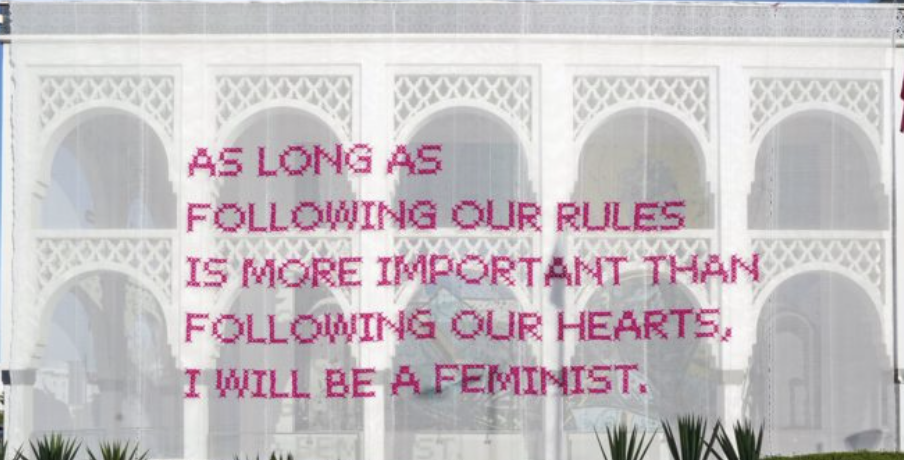

One of my favourite contemporary female artists who incorporates weaving into her work, is the Austrian artist and activist, Katharina Cibulk, who in her ongoing project, ‘Solange’, embroiders monumental feminist messages on to buildings.

Leave a Reply