Beasts of Burden” Exploring the relationship between Animals, Communication and Ableism

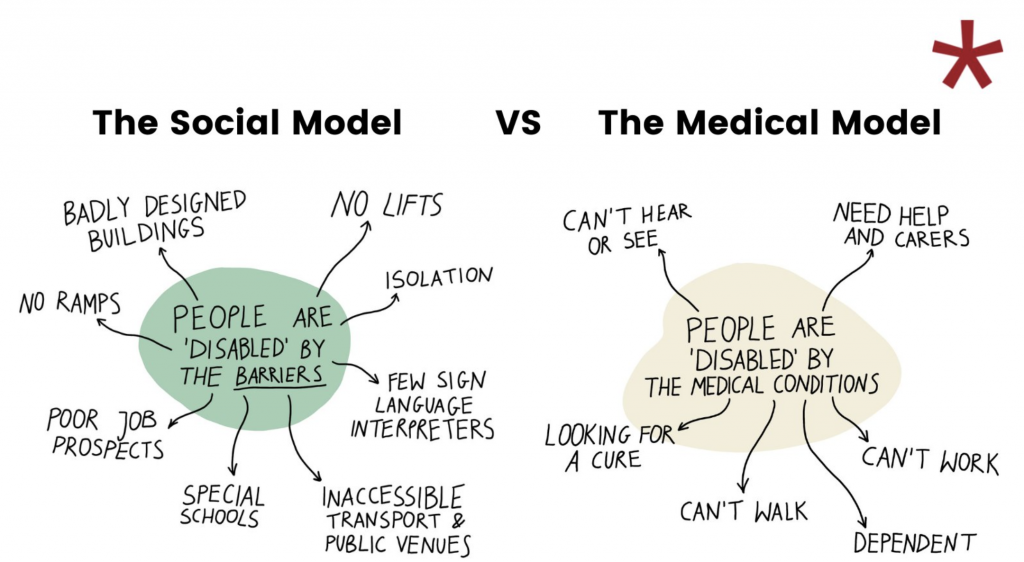

The book Beasts of Burden by Sunaura Taylor explores the intersection between animals and humans and how that links to ableism. Taylor has a disability called, “arthrogryposis,” and when she was growing up other children often compared her to an animal, they would say walked like a monkey or she ate like a dog; by this, they meant that her disability made her like an animal and, therefore, less than human. Taylor argues in Beasts of Burden that humans are animals because, ‘age disease and accident mean that all able-bodiedness is a temporary state. Even able-bodied people ‘die in the woods’ alone – they, too are dependent upon society.’ In this way Taylor looks at disability using the social model. This model says individuals are disabled because of barriers put up by society rather than by their own impairments, these can be physical barriers like accessibility or barriers caused by people’s attitudes. ‘Disability appears in the interaction between the impaired person and the social environment.’ The social model sees these barriers as things that make life harder for disabled individuals and thus removing these barriers will lead to greater equality e.g. someone is not disabled because they use wheelchair rather they are disabled because the world is not built in a way that is accessible to wheelchair users. Therefore, if we take this view, society is what makes people disabled and disability becomes a form of social oppression. In the book Taylor puts forward the argument, ‘If you’re cognitively or physically disabled, it’s ableism that tells you that you’re worth less than a more capable person; similarly, if you’re an animal, it’s ableism that makes eating you permissible, since you can’t do what humans do.’

Language and Communication

In Disney some animals are amorphized whilst other animals of the same species are objectified. The most famous example is Goofy and Pluto, both are dogs, but one is treated like a human and the other like a pet. Goofy is one of Mickey’s best friends and Pluto is his pet dog. Goofy has a job, drives, can orally converse using spoken language and walks upright on two feet. Pluto on the other hand is disabled, he walks on all fours and can’t speak, he is therefore forced to wear a leash and sleep in a dog house, he is enslaved within the ableist society of Mickey Mouse. This dynamic is interesting because it makes you think critically about how we as humans treat animals. This is because cartoons are ‘morphable’ and ‘even quite resolutely andromorphic animal characters can end up putting human exceptionalism into question.’

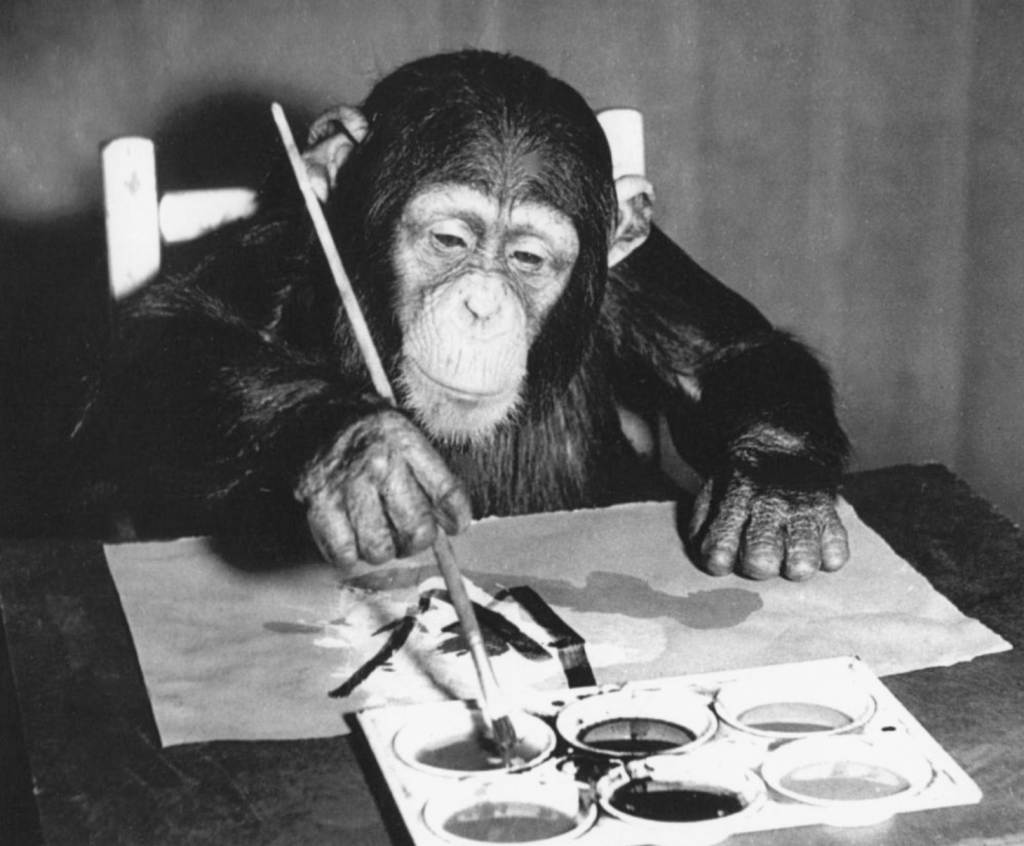

Within mainstream society spoken language is often viewed as superior to non-verbal communication. This is an ableist way of thinking. For a long time, sign language was regarded as a non-complex or primitive form of communication. Sign language is a good example of how, ‘race, disability and animality have been entangled.’ For a long time, people believed that you had to be able to hear, to be able to communicate. Aristotle held the belief that ‘hearing was necessary for speech, which he believed was central to thinking.’ Therefore, he concluded that because deaf people can’t hear this makes them incapable of complex thought and intelligence. This belief is what lead to a long legacy of deaf people being treated as ‘animal-like or less-than-human.’ It took a long time for these views to begin to be dismantled, not until 1760 would sign language even be taught in schools to deaf students. Further, sign language was viewed as a primitive mode of communication. Moving into the 19th century there was a rise in evolution theory and sign language generally became seen as the language used by ‘savages’ and other ‘inferior people.’ Sign language then became racialised and related to people of colour, as both were regarded as primitive. Sign language was typically described using, animal metaphors, particularly those referencing monkeys and apes. It was argued that sign language could not be considered on the same level as spoken language because it was gestural and therefore, ‘it could no more be called a language than expressive animal movements like the wag of a dog’s tail.’ We must ask why the wagging of a dog’s tail is not a valid form of language. Research has shown that dogs have different tail wags that mean different things based on, ‘the tails pattern of movement and position.’ A dog’s tail wag can show they’re happy, excited, nervous or can even be a warning, for example a dog’s tail tucked under their body is sign that they’re scared. Dogs don’t wag their tails when they’re alone because it’s a mode of communication, a ‘social signal.’ There are so many complexities, speed of wag, breadth of each tail sweep. Dogs eyes are more sensitive to movement; tail wagging is an important mode of canine communication. Often people see spoken language as superior so instead of attempting to learn how to communicate with animals in their own complex communication systems, or ways they understand, instead we impose our language onto them and if they don’t understand they are viewed as unintelligent. This is an example of how people who communicate differently are othered within society.

Anne Mcdonald was born in the 1960s in Australia and was institutionalised after an injury during her birth caused her to develop cerebral palsy. At age three, Anne couldn’t walk, talk or feed herself, she was deemed to be severely disabled and sent away to St Nicholas Hospital for severely disabled children, where she and many other disabled children were starved and neglected. As most of the residents couldn’t communicate orally and nobody attempted to find a way to communicate with them, this abuse carried on largely unquestioned. However, when Anne was 16, a student called Rosemary Crossely came to the institution because she needed a subject for a project she was doing for her Bachelor of Education degree. Rosemary helped Anne learn to communicate through an alphabet board by pointing to letters to spell out sentences. Once Anne was able to communicate, she made her wishes to leave the institution known. However, in after that she still had to go to the Supreme Court and fight for her right to leave the hospital because the hospital and her parents didn’t feel her communication was legitimate, this furthur serves to prove how people discredit different modes of communication as illegitimate. Luckily the court ruled that Anne’s communication was her and own at age 18 she was allowed to leave the institution. However what about all the people who got left behind? One could tentatively compare Anne’s story to that of Boee the chimpanzee who was born in the National Institute of Health in 1967.

Boee was given experimental split-brain surgery as a baby, which left him very poorly and in a lot of pain. Roger Fouts, the head primatologist at the Insititute felt sorry for the baby chimp and took him home. However, soon the baby chimpanzee grew far too big to live in a family home and so was sent to Oklahoma to the Institute of Primate studies. It was here that Boee learnt American Sign Language learning more than fifty words, how to form sentences and ask and answer questions. There was another chimp there called Washo, who Fouts also taught. Fouts began to see how dangerous the Institute was for the animals who lived there. Dr William Lemmon who ran the Institute, was notorious for how he abused the animals in his care. Fouts found a way to take Washo and leave, however he regretted that he couldn’t take all the chimps with him as they belonged to Lemmon and the Institute. Boee got left behind. In 1982, Lemman sold many chimpanzees including Boee to the Laboratory for Experimental Medicine and Surgery in Primates (LEMSIP.) This is the institution that is featured in the documentary Project Nim about the chimp Nim Chimpsky who had also also been sent to the institute by Lemman. Nim Chimpsky had been brought up like Boee in a family home as part of Project Nim which aimed to explore what would happen if you brought up a chimpanzee like a human baby. When the public found out that Nim had been put into a research institute there was a huge outrage. ‘The outcry over Nim and Ally [another famous chimp being held at the institute] was not about the chimps themselves but about the imprisonment of beings who possessed highly “human” traits.’22 The public rallied against LEMSIP and Nim was released. The public didn’t know about Boee and with the release of Nim, ‘Boee’s chances of being freed evaporated.’ Boee spent the next thirteen years of his life at LEMSIP, living in a cage and being injected with Hepatatis C for research. Did Boee not deserve our compassion before he could speak American sign language? Why is it ok for chimpanzees that cannot speak sign language to be kept in cages their whole lives and experimented on? If we only link humanity to being able to communicate then what about all the beings who can’t speak or sign? When Mcdonald talks about her time in the institute she says, ‘The nurses didn’t know what to do; they didn’t know we could feel anguish.’24 This inability to communicate with the nurses is what probably contributed to the inhumane treatment the children at the hospital endured. The children couldn’t communicate with the nurses, so they were dehumanized and objectified. Mcdonald argues that the, ‘humanity we share is not dependent on speech.’

Personhood

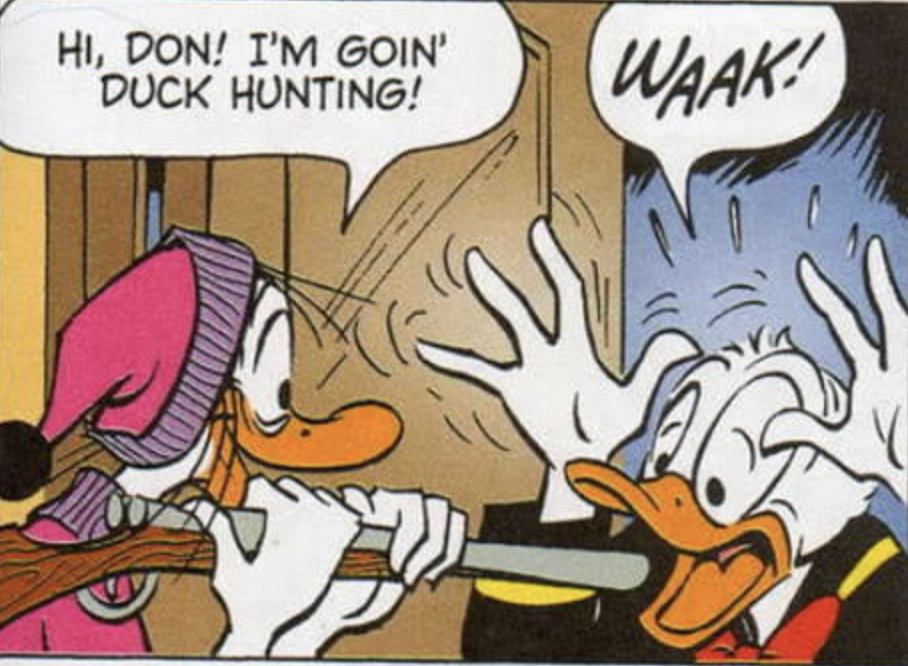

Another example from Disney is the Mickey Mouse comic where Donald Duck goes duck hunting, he justifies this by saying because these ducks can’t speak, it’s ok to kill them. We can look at this in relation to the writing of the utilitarian philosopher Peter Singer who argues in his book Animal Liberation that all sentient beings deserve equal consideration because animals and humans all feel pain equally. Further there are, ‘no morally relevant abilities that all animals don’t have but all animals do.’ You could use language as an example, ‘not all animals have language but not all humans have language either.’ Singer argues that the pain felt by a human is no worse than the pain felt by an animal, but he goes onto also say that not all ‘individuals are equally valuable.’ Therefore, it’s ok to kill animals if it’s done in a humane and non-painful way because animals have less ‘personhood’ than humans. Singers argument is that ‘personhood’30 is defined by how much cognitive complexity a being has, this is understood by their ability to comprehend time and death and their relationship to these concepts. It’s about how much value, ‘that being will place on keeping itself alive.’ Having goals and plans and experiencing oneself through time, ‘the loss of a human’s unfulfilled dreams adds to the wrongness of his or her death.’ Whereas, Singer would argue most animals don’t experience time beyond their next meal or next sexual encounter. Steven Best explains Singers notion of ‘personhood’ as ‘the possession of traits like the capacity to feel and reason, self-awareness and autonomy and the ability to imagine a future.’ Singer, as a utilitarian would argue that, it would not be wrong to humanely kill these less ‘complex’ beings if the, ‘good consequences of doing so out-weigh the bad.’ Many writers have built on Singers argument to justify why it’s not bad to eat animals if they’ve come from, ‘good farms.’ However, how can we even determine which animals have ‘future orientated interests’36 and which don’t. Bears prepare for winter, by eating more, is this not a form of preparing for the future and therefore having ‘future orientated interests?’ A criticism of ‘personhood’ would be that it privileges a Western notion of time, ‘which is rooted in progress and future orientated goals.’ Especially when you consider, ‘crip time’ and the notion that we ‘live at different speeds and out sense of time is shaped by our experiences and abilities.’ Therefore, time is relative and one could argue that ‘personhood’ is an ‘ableist, neurotypical and speciest’ concept. However, there are people who argue that it’s problematic to compare animal and humans because it flattens both ‘communities into stereotypes and says nothing of their differences.’ Especially when we compare the intellectually disabled to animals, the argument sometimes becomes, ‘if the animals go down, so should the intellectually disabled.’

Another argument is, would it be ok for Donald Duck to kill the non-verbal ducks if it could be proven that they lacked ‘personhood?’ Singer would argue yes, if Donald Duck killed the ducks in a non-painful way and their deaths brought happiness or joy to Donald who does have ‘personhood’ then killing them would be morally ok. One could also argue that, Donald Duck saying that it’s ok to kill these ducks because they can’t speak is harmful because it connects ‘personhood’ to oral communication and therefore beings who can’t speak or are mute are considered less than if we use Singer’s framework. Also, ducks do speak they just communicate differently, research has shown that ducks use complex combinations of vocalization and body language. Ducks are also capable of abstract thought, they can differentiate between concepts of difference and sameness. Singer uses the example of a house fire, where he must decide whether to save a human or a mouse. He would save the human because people, ‘have more to lose’ this is because we can comprehend our life, we have a past, present and future and he’s not sure mice have the same sense of ‘existing over time.’ Humans have families that would mourn their lose. In general, the greater lose would be the human but we must also consider all the humans who lack the cognitive complexity to have ‘personhood.’ Singer would see these people as not full humans and their deaths, if painless, as justifiable. This includes infants, unborn babies and people with severe intellectual disabilities. Therefore, we have some cases where humans wouldn’t have ‘personhood’ or be considered ‘persons’ like the case of babies born with half a brain and animals like gorilla’s or chimps would be considered ‘persons.’ If given the same option to save the mouse or a brain damaged or severely disabled human, Singer argues that it ‘might not be better to save the human.’ An example of this, given by Singer is if a couple has a severely disabled baby, then killing that baby would be morally ok, if they would go on to have a healthy baby that would provide them with more happiness over time. However, most babies who are healthy are loved and wanted and therefore killing them, even painlessly, would be wrong because it would bring their parents great distress.

To conclude it’s interesting to look at the parallels we can make between having rights and being able to communicate our rights orally. It leads me to think if all animals could speak, would they be afforded the same rights as humans? If that is the case, then we should consider their lives equally the same way we consider humans who cannot speak or are differently abled equally.

Works Cited

Coren , Stanley. What a Wagging Dog Tail Really Means: New Scientific Data.December 2011. https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/canine-corner/201112/what-wagging-dog-tail-really-means-new- scientific-data.

Crossley, Rosemary. , The right to communicate; a battle not yet won.May 2011. http://www.abc.net.au/rampup/articles/2011/05/24/3224584.htm.

Heise, Ursula K. Plasmatic Nature Environmentalism and Animated Film .April 2014.

Mcdonald, Anne. Fourteen years in an institution.http://www.annemcdonaldcentre.org.au/anne-14-years-st nicholas.

Morrel, Virginia. Video: Ducklings capable of abstract thought.2016.

https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2016/07/video-ducklings-capable-abstract-thought.

People with Disability Australia. Social Model of Disability.https://pwd.org.au/resources/social-model-of-disability/.

Peter Singer. frequently asked questions.https://petersinger.info/faq.

Rothman, Joshua. Are Disability Rights and Animals Rights Connected?June 5th, 2017. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/persons-of-interest/are-disability-rights-and-animal-rights-connected.

Samuels , Ellen. “Six Ways of Looking at Crip Time, Disability Studies Quarterly.” disability studies quarterly.2017 . http://dsq-sds.org/article/view/5824/4684.

Singer, Peter. Animal Liberation.1995.

—. Equality for Animals? Excerpted from Practical Ethics.1979. https://www.utilitarian.net/singer/by/1979—-.htm.

Taylor, Sunaura. Beasts of Burden, Animal and Disability Liberation.The New Press, 2017.

Leave a Reply